My Story

I was born in Casper, Wyoming in 1951. My father, Walter Gray Davis, was born in 1907 and grew up in East Texas; and my mother, Robbie Elizabeth Peyton, arrived in the world in Northern Louisiana that same year. My fathers’ parents had land, about 120 acres, that they farmed for a living; they were dirt poor during his childhood. He sold goods in various country stores from early teenager-hood to supplement the family income he made it through the Great Depression selling White King soap to hotels, driving his truck with the company logo all over Texas and northern Mexico, and wow did he have some stories to tell about staying in saloons in those border towns! He learned to stay out of bar fights that didn’t concern him by always sitting in a corner, where he could pull the table around him for protection if a fight broke out. So he taught me always to sit with my back to the wall so I could see trouble coming, and to this day I get nervous if I can’t see the room. His favorite saying, which I had engraved on his tombstone, was “Never let the sun rise tomorrow on what you can do today” and I try to live up to that.

Robbie’s Mother

Robbie’s Mother

She graduated from high school at the age of 15, then from business school, and went to work at the age of 17 as a secretary, first in Shreveport and later in San Antonio, Texas. There my parents met and maried one year later, in 1936. She and Daddy both had high aspirations for their lives, so when Amerada Oil, the company my mother worked for, had an opening in California for an enterprising land man (oil scout), she recommended my dad and he was hired.

Baby Robbie

And so I was born in Casper—the miracle child who finally arrived after my mother had had several miscarriages while living in California. The California doctors had insisted that she spend her pregnancies in bed, because of her extreme nausea and weakness, but she lost those babies, so when the country doctor in Casper, Fred Haigler, told her to just ignore all that and “Rise above it” she took his advice and went out as much as always (he told her to run to the bathroom and throw up if she had to, then to wash her face and go right back to the party!). I was born by what we now call “scheduled cesarean.”

Baby Robbie

Mom, Dad, and Robbie, age 7

Mom, Dad, and Robbie, age 7

After that, her life mantra became “Rise above it!” —those words have stood me well many a time. I almost put them on her tombstone, but could only imagine how funny that would look to a passerby. So instead I put on her tombstone what she asked me to before she died: “She was a slave to beauty, in all of its forms, for all of her life.”

Cowgirl Robbie

We moved to San Antonio, Texas where my parents had friends and family when I was 8; my parents were tired of the long cold winters and my dad felt by then that he could manage his business from afar. What a massive change for a small-town girl!

Cowgirl Robbie

Robbie, age 16, at the Alamo

Robbie, age 16, at the Alamo

I got into Wellesley through early admission, but only spent one year there as I became engaged to and maried Russell Johnson, who was in college at UT Austin, so I joined him there and completed my BA, MA, and PhD at the University of Texas. The UT Plan II program was perfect for me—it took away the bewilderment of finding myself at such a huge university, gave me a home where my advisors always knew me by name, and opportunities to take a wide variety of

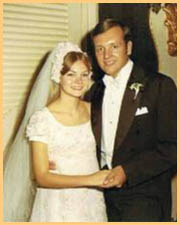

Robbie and Russell Johnson

For the law course, my student partner and I studied why the townspeople and even the Sheriff allowed the Chicken Ranch to exist (it had to do with their Bohemian and Slovakian heritage, which was much more accepting of such institutions than WASPy types tend to be). For the folklore course, we spent hours listening to the Madam, Edna Milton, tell jokes and folktales, and studying how she maintained verbal control of the girls, their customers, and the general environment through folklore and storytelling. I wrote my master’s thesis about her, and later an

When Russell graduated from law school, we moved to Dallas, but the life of the wife of a Highland Park attorney wasn’t for me, so we divorced and I moved back to Austin to go for my PhD in Anthropology. Needing to learn a second language (a requirement for the PhD), I made a side trip to Mexico, where I studied and learned Spanish and discovered a world of such rich traditional cultures in such fascinating interaction with modernization and change that I stayed for a while, studying two Mexican shamans and writing a long paper about shamanism in Mexico, which someday I hope to revamp and publish.

Robbie and Russell Johnson

My Dissertation and First Book

By the time I had to pick a dissertation topic (I had thought it would be shamanism), I had married Robert Floyd, an Austin architect, and we had given birth to a baby girl, Peyton. What I had planned and hoped would be a natural birth in the hospital turned into a highly traumatic cesarean, leaving me full of questions about why hospital birth is the way it is—so technological and interventionist. I began asking other women about their birth experiences, got fascinated, and went on to interview 100 women about their experiences of pregnancy and birth, which first was my dissertation and then, after various articles and years of work, became my first book, Birth as an American Rite of Passage (1992). As I struggled with each page in one of the greatest labors of love of my life, I had no idea whether anyone would even read it. So I was stunned and overjoyed when, shortly after it came out, it was given a glowing review by Sarah Ruddick in the Sunday New York Times Book Review and many other places, and it went on to be widely used for teaching in anthropology, women’s studies, sociology, American studies, and midwifery education courses, and to be called a “classic in the field.” Much to my ongoing delight, a famous anthropologist, Charles Leslie, wrote an overview of medical anthropology in which he called my book “a mountain in the landscape” of the field. Wow!

UC Press gave me a contract in 1987, and waited patiently for the final manuscript, which I finally sent in three years, six courses (I was teaching part-time), nine articles, hundreds of lullabies, and thousands of laundry loads later. I remain deeply grateful to my UC Press editor, Stanley Holwitz, for his patience and his enduring support and friendship, and to my children, Peyton and Jason, for their tolerance of my always being late to pick them up at school and the day care center. (I am sure that the fact that my son is always on time for everything is a lasting legacy of my lateness, which he continues to bring up whenever he gets a chance!)

The Emergence of my Interests in Midwives, Holistic Physicians, Futures Planning, and Aerospace Engineers

After the book came out, speaking invitations came pouring in. Through the talks I gave at many childbirth and midwifery conferences, I discovered midwives in their numbers and became fascinated with these amazing women who give such nurturant and loving care to women during their births, at home or in the hospital. So, while continuing my research on women, I began also to study midwives—their practices, ideologies, politics, and identities in a changing world. Many of the articles I wrote about them are available on this website, and my book on American midwives (Mainstreaming Midwives: The Politics of Change) came out from Routledge in 2006.

Invited one year to speak to the American Holistic Medical Association about birth, I immediately found myself fascinated by the holistic physicians surrounding me at that conference—why, after so many years of medical training, would they choose to “shift paradigms” and learn other healing modalities? I pulled out my tape recorder and did my first set of seven interviews on the spot. (Anthropology is so cool—it gives you the tools to study anything that turns you on!) When I met Gloria St. John, a homeopath and former hospital administrator who had been running support groups for holistic physicians in the Bay Area, I knew we should do this one together.

Our forty interviews with holistic docs led to a book we are very proud of, From Doctor to Healer: The Transformative Journey. It identifies the three paradigms of health care across which physicians shift—the technocratic, humanistic, and holistic models; describes the catalysts that spark them to take this transformative journey; and illustrates how they practice after they have completed their journey and integrated holistic ideologies and modalities with what they choose to retain of traditional medicine. This book finds its best use in the alternative medicine courses taught in medical school and with physicians dissatisfied with practicing technocratic medicine who want more ample healing abilities. Many docs who have read it have written to express their appreciation (“Finally I understand what happened to me in medical school, why it made me feel so limited, and what I can do about it!” I continue to receive very gratifying letters from my former medical students at Rice Univerity saying that my teachings were “a gold nugget that they carried in their pockets all through medical school” and made them better doctors in the end.)

I taught medical anthropology at Rice University several times, to replace my dear friend Nia Georges when she went on sabbatical. The chair of the Rice Anthropology Department, George Marcus, was in the process of doing a book called Corporate Futures, and invited me to participate. Looking to broaden my ethnographic and knowledge base, I undertook a study of a group of aerospace engineers (the group was called SATWG—Strategic Avionics Technology Working Group, later changed to ATWG), focusing on their “vision for commercializing outer space.” At first I envisioned giant McDonalds orbiting the planet, but soon found that they meant more launch vehicles to get more satellites into outer space—it was all about global communication systems. Fascinated by their own fascination with technology (I asked one engineer, “What are the limits of these technologies” and he answered, “There are no limits!!), I wrote an ethnography of this group and its visions (“The SATWG Stories,” available on this website).

In the same vein, I conducted an extensive interview with Betty Sue Flowers about her directorship of the writing of Shell International’s futures scenarios—stories about the future, based on present trends and data collected from all over the world. Realizing that straight line projections can never account for future variables, Shell wisely dropped such “objective projections” in favor of writing two or three stories about the future every few years—each story a reasonable and possible scenario for what might happen. Having more than one story available as “good for thinking” makes Shell workers sensitive to what they call “weak signals” from local or global events that indicate that one or another story might be unfolding. These scenarios have enabled Shell to guess right about the future often enough to become one of the largest and most successful energy companies in the world, and have sparked a whole industry of scenario-writing, as other companies and entities have realized the value of such futures scenarios. My article, “Storying Corporate Futures: The Shell Scenarios” (available here) encapsulates the magic of this process and its ongoing results, which now include the realization that a sustainable future for any company will depend on the sustainability of the environment.

My work with SATWG (a NASA-industry-academe interface group) led to invitations from NASA employees to conduct multiple oral histories with pioneers of the American space program—not with astronauts, who have been often interviewed, but with the scientists, engineers, designers, and managers of the early space program. My co-interviewer Kenneth C. Cox, a long-time NASA engineer, our friend Frank White, and I are very close to finishing a book containing these interviews, to be called Space Stories: Oral Histories from the Pioneers of the American Space Program.

In the meantime, two of our completed interviews appear on this website, with Guy Thibodaux, rocket scientist, Max Faget, designer of the early space capsules and of the first versions of the space shuttle, and Paul Purser, their boss at Langley Field in the last days of the NACA and the early days of NASA. Once the book is out, I will be able to publish the full text of all the other interviews on this website as well. (The stories in the book will be radically condensed; the full texts will appear here.) Our other interviewees include Caldwell Johnson, Eilene Galloway, Paul Dembling, Chris Kraft, Clotaire Wood, Josephine Dibella, Adelbert Tischler, and Harry Finger.

Teaching

I have taught both general and specialized forms of cultural anthropology for over 20 years, at various universities. I love teaching and working with students, which I continue to do as advisor for independent study projects, dissertation committee member, or external examiner. For the present I am retired from teaching more than the occasional course from time to time, but I am still open to that “perfect job”—the one that might be waiting for me somewhere at a wonderful university or small college, with interested and committed students, congenial faculty members, and the opportunity to teach a wide range of courses, from introductory to advanced. Should that job ever materialize, I will commit my life to doing it well. In the meantime, I am fulfilled and busy with writing and traveling to conduct research and to give talks all over the world.

My ongoing research addresses postmodern midwives in Mexico (see “Daughter of Time: The Postmodern Midwife” on this website), the ideologies and practices of holistic obstetricians, the use and abuse of scientific evidence in medical practice, global trends and developments in midwifery, and the movements in many countries to humanize childbirth and medical practice. While holism remains scorned by most technocratic physicians, and fully practiced by only a few, humanism as ideology and practice is gaining groundswell support around the world (see my article “The Technocratic, Humanistic, and Holistic Models of Birth” on this website, and From Doctor to Healer for more complete explanations.) While I am a proponent of holism, I see humanism in health care (which includes public health initiatives) as the most viable hope for the development of health care systems that respond to people’s actual and most pressing needs.

A Personal Note

Since September 12, 2000 I have had to cope with the death by car accident of my daughter, Peyton Elizabeth Floyd. Although I have lost to untimely death my parents, various relatives, and some of my dearest friends, I find that none of this compares to experiencing the death of a child. I have recorded something of what that has been like in an article “Windows in Space/Time: A Personal Retrospective on Birth and Death” (available here) and eventually hope to write a book, Grieving and Grace: A Deep Description, which will tell hard truths about what it is really like to lose a child. I also offer on this website a short primer called “The Art of Grieving Gracefully” for those in need of some advice about the grieving process.